The Evolutionary Epiphany That Shook the World

Darwin and Wallace's independent realization of the mechanism by which new species might emerge from existing ones was a concept entirely new to the world.

In the tranquil Victorian-age English countryside, a young Charles Darwin found himself engrossed in the musings of his grandfather, Erasmus Darwin. The elder Darwin had penned "Zoonomia," a work that ventured into the realm of species transformation. "Would it be too bold to imagine," Erasmus pondered, "that all warm-blooded animals have arisen from one living filament?" This was the late 1820s, and Charles was a student at Christ's College, Cambridge. The musings of his grandfather served as one of many stepping-stones in a journey that would lead to one of the most groundbreaking theories in the history of science.

Years later, Darwin’s father-in-law gave him some fossils of an extinct mastodon, impressing upon Charles that things in the past might have been rather different than the present. His penchant for learning about nature set him on a course that included five major overseas journeys that would cause him to come to understand one of the greatest principles of biology.

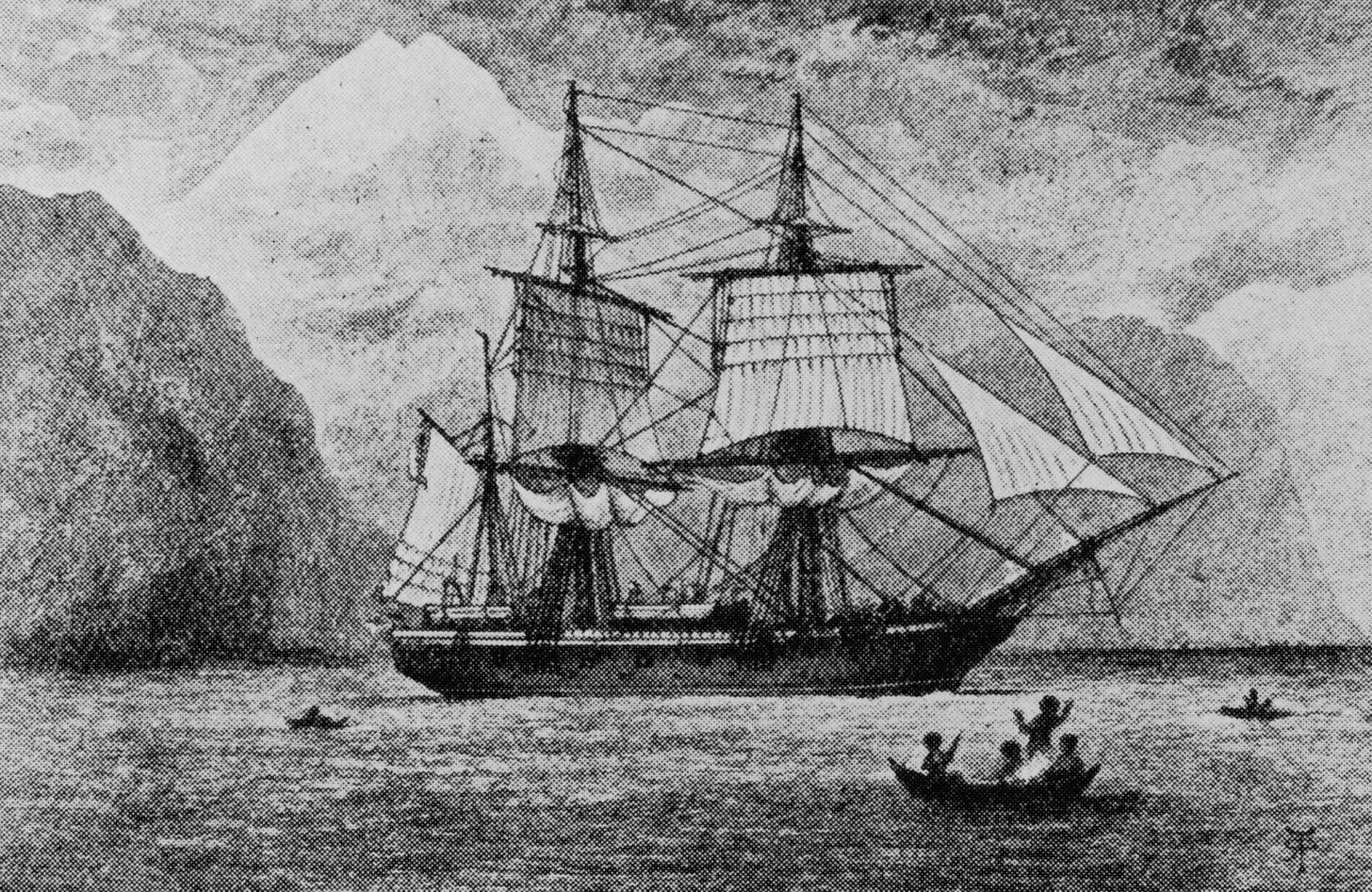

In the decades prior to Darwin's overseas explorations, the scientific community was already abuzz with various theories and speculations about the transmutation of species. Just prior to the Victorian Age, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck had proposed a form of evolution driven by acquired characteristics, though his ideas were largely dismissed, especially in light of the counterargument that the sons of blacksmiths did not inherit their fathers' muscular arms. The anonymously published "Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation" had stirred public interest in the idea of transmutation of species, but it lacked empirical evidence and was considered speculative at best. Sir John Sebright's work on animal breeding had shown that traits could be selected for, but this was in the realm of artificial selection, not natural processes. Geologist Charles Lyell, while not a proponent of transmutation, had opened minds to the idea of a much older Earth where changes could accumulate over long periods. Thomas Malthus discussed in his Essay on the Principle of Populations the struggle for existence due to population pressures, but his ideas had not yet been applied to the natural world in the way that Darwin would later do. Various concepts of species transformation were thus in the air, but it was fraught with controversy and lacked a unifying theory. These were the prevailing winds into which Darwin set sail, a young man on the ship HMS Beagle, bound for the unknown, bound for discovery.

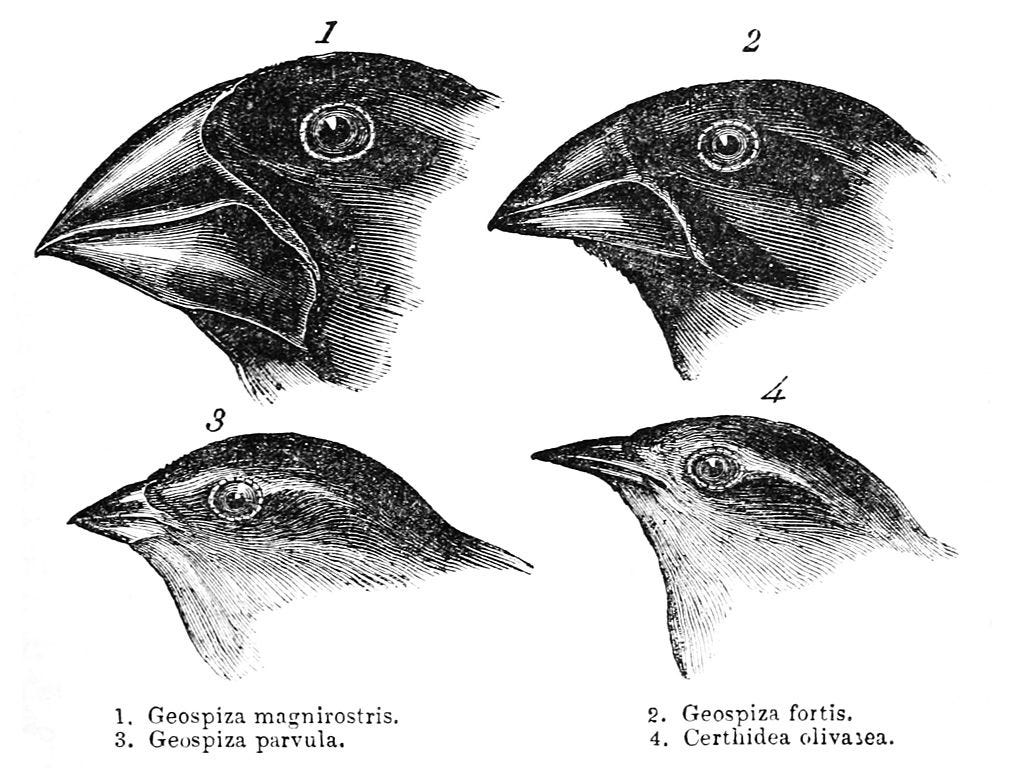

By the early 1830s, Darwin had embarked on the Beagle, a voyage that would take him to the far reaches of the Earth, including the Galápagos Islands. Here, he encountered finches with varying beak shapes and sizes. "The most striking and important fact for us in regard to the inhabitants of islands," Darwin later wrote, "is their affinity to those of the nearest mainland, without being actually the same species." (Origins, 1859). The variation among the finches, the tortoises, and the iguanas, and the association of the variation with geography spoke to Darwin. Darwin presumed these variations emerged after an ancestor descended from ancestral stock on the mainland of South America. The accumulating evidence all seemed to whisper the same secret: species could change over time, and the changes that remain were related both to geography and to the environment.

All along his life, and even on this journey, young Darwin's mind was repeatedly primed with thoughts on species transformation. During his voyage on the Beagle, he read Lyell's "Principles of Geology," a work that described evidence of slow and gradual change of the Earth's surface over time. "He who can read Sir Charles Lyell's grand work on the Principles of Geology," Darwin noted, "yet does not admit how incomprehensibly vast have been the past periods of time, may at once close this volume." Lyell's work was a revelation; it provided Darwin with the temporal canvas on which the brushstrokes of evolution could be painted.

What was lacking for Darwin and other naturalists of him time was a viable mechanism by which seemingly fixed species could change over longer periods of time. Of all of his exposures, Darwin also recalled the massive impact of his reading of Thomas Malthus, whose "An Essay on the Principle of Population" provided most of what Darwin needed for his concept of natural selection. The concept was of the "struggle for existence." It was Malthus's ideas on the consequences of population overgrowth in the face of limited resources that gave Darwin the framework to understand how natural selection could operate. "Nothing is easier than to specify cases where an animal or plant in any country would have been better fitted, than it is, for its conditions of life," Darwin mused. Malthus's work was the missing puzzle piece that Darwin needed; it was the mechanism that drove the change he had observed in species. "Here, then, I had at last got a theory by which to work," Darwin would later write in his autobiography.

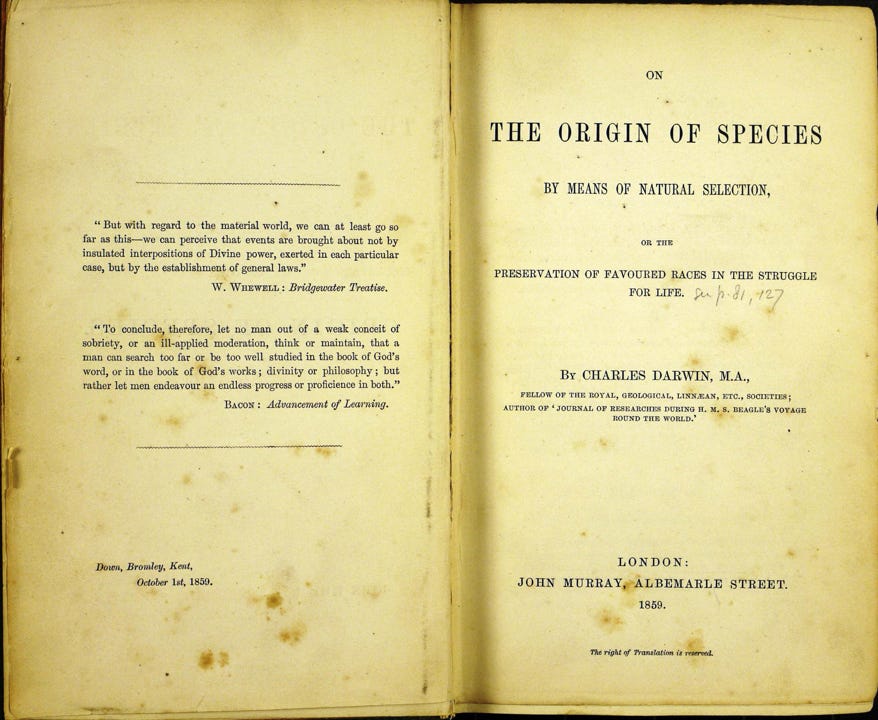

By the late 1830s, Darwin had returned to England and was, in between bouts and illness, meticulously compiling evidence. He studied pigeon breeding, an example of artificial selection, and noted, "When we look to the hereditary varieties or races of our domestic animals and plants, and compare them with species closely allied together, we generally perceive in each domestic race, as already remarked, less uniformity of character than in true species" (Origins, 1859). He examined fossils of the Silurian period, including trilobites, and concluded, "Consequently, if my theory be true, it is indisputable that before the lowest Silurian stratum was deposited, long periods elapsed, as long as, or probably far longer than, the whole interval from the Silurian age to the present day; and that during these vast, yet quite unknown, periods of time, the world swarmed with living creatures" (Origins, 1859).

Darwin also referenced evidence from embryology, mentioning the similarities in the embryos of vertebrates. "Thus the embryo comes to be left as a sort of picture, preserved by nature, of the ancient and less modified condition of each animal," he wrote. In the realm of insects, he noted the "wonderfully close" resemblance of the stick insect to twigs, a marvel of mimicry and camouflage. "This resemblance is wonderfully close, a profusion of twigs projecting from the heaths, and the elytra of this beetle being furnished with long spines, an exact imitation of them," Darwin observed in Origins (1859).

From comparative anatomy, it was apparent to Darwin that it would be inefficient and unnecessary to design flippers of large sea mammals like whales from hand-like structures. "What can be more curious than that the hand of a man, formed for grasping, that of a mole for digging, the leg of the horse, the paddle of the porpoise, and the wing of the bat, should all be constructed on the same pattern?" (Origins, 1859).

It was during this period that Darwin also became acquainted with the work of Sir John Sebright, who had written extensively on animal breeding. Sebright's observations on the heritability of traits in domestic animals further solidified Darwin's understanding of variation and selection. Darwin was now armed with a plethora of evidence, but the synthesis of these ideas into a coherent theory eluded him. That is until an epiphany struck him while riding in a carriage. The realization that natural selection was the driving force behind the evolution of species dawned on him, and the pieces of the puzzle finally fell into place.

In the tapestry of Darwin's theory, each thread of evidence—be it the finches of the Galápagos, Lyell's geological timescales, Malthus's essays on competition for resources for survival and for existence, or the mimicry of stick insects—wove together to form a coherent picture. It was a picture painted on a canvas that spanned eons and stretched across disciplines, a picture that finally made sense of the bewildering diversity and complexity of life on Earth.

For all of his knowledge, little did Darwin know that after over 20 years of work on a theory, another naturalist from England was close on his heels. Alfred Russel Wallace, a man of humble beginnings but towering intellect, was about to send a ripple through the scientific community that would forever link his name with that of Darwin. Both men were shaped by similar influences—Malthus's theories on population, Lyell's principles of geology, and the prevailing yet debated ideas on transmutation. Yet, their paths to the theory of natural selection were as divergent as the species they studied.

Wallace, born in Usk, Monmouthshire, was the youngest of nine children in a family of modest means. His formal education was cut short, but the fields and woods became his classroom. "Pure enjoyment," he would later describe his time surveying the land for his brother's business. Darwin, on the other hand, was born into a family of considerable means and had the privilege of a formal education and even considerable influence on his views of evolution from his father-in-law, who gave Darwin a mammoth fossil. Yet for all of their differences, both Wallace and Darwin were united by an insatiable curiosity about the natural world.

As a young man, Wallace found employment with his brother, John, surveying the countryside for potential railway routes. It was a job that allowed him to wander through fields and woods, observing the natural world in all its splendor. When his brother's surveying business failed, Wallace took up teaching, a profession that neither suited his temperament nor quenched his thirst for knowledge. It was during this period that he met Henry Walter Bates, a fellow naturalist and kindred spirit.

The friendship between Alfred Russel Wallace and Henry Walter Bates was a pivotal moment in Wallace's life, both personally and scientifically. Bates, like Wallace, was a passionate naturalist, and their shared interests in biology and taxonomy provided a fertile ground for intellectual exchange. Bates was already an established entomologist when he met Wallace, and his expertise in the field likely influenced Wallace's own interests in collecting and studying insects, particularly butterflies.

Moreover, Bates himself is known for the "Batesian mimicry" concept, an idea that certain species evolve to mimic the appearance of more dangerous species to deter predators. This concept likely influenced Wallace's own thoughts on mimicry and natural selection.

Bates not only provided Wallace with companionship and intellectual camaraderie but also played a significant role in shaping his scientific pursuits. Their friendship would prove to be a pivotal moment in Wallace's life.

Their friendship led to a collaborative expedition to the Amazon in 1848, a journey that would prove transformative for Wallace. Inspired by the explorations of Alexander von Humboldt and Charles Darwin, Wallace and Bates set out on an expedition to the Amazon in 1848. During this expedition, Wallace collected a vast number of specimens and made detailed observations that would later inform his theories on natural selection and biogeography. The Amazon expedition was a formative experience, providing Wallace with the empirical data he needed to formulate his ideas on species variation and distribution. Bates would recount his ventures in “The Naturalist on the River Amazons” in 1868

For four years, Wallace collected specimens, which he sent back to what is now modern-day Manaus, along with recorded observations, and immersed himself in the untamed wilderness. Tragically, on his return journey, his ship caught fire, and he lost nearly all his collections. Undeterred, Wallace penned his experiences in "A Narrative of Travels on the Amazon and Rio Negro," a work that caught the attention of none other than Charles Darwin.

Wallace's journey to the Amazon was both a disaster and a revelation. While returning the United Kingdom, his entire collection was lost when the ship caught fire and sank. By some great stroke of luck, Wallace and other survivors were picked up by a freighter, which also nearly sank and was woefully short of stores given the extra passengers. Wallace managed to save only a tin with a few of his shirts and two sketches.

Undaunted, Wallace returned with a resolve to understand the mysteries of life's diversity. "In all works on Natural History, we constantly find details of the marvellous adaptation of animals to their food, their habits, and the localities in which they are found," Wallace would later write, reflecting upon his observations during his travels.

One of Wallace's most groundbreaking discoveries came during his expedition to the Malay Archipelago, where he identified a faunal boundary line separating the ecozones of Asia and Australia. Specifically, Wallace expected to find the same types of mammals on two islands close to each other, with the same climate, the same soil type, etc. Yet upon traveling between islands, he discovered that the western island had placenta mammals on the ground and in the trees while on the eastern island, marsupial mammals inhabited the same niches.

The geographic demarcation, later known as Wallace's Line, was a revelation that helped him focus his theory on the introduction of new species. "Every species has come into existence coincident both in space and time with a pre-existing closely allied species," (Wallace's essay on varieties, published in the Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society (Zoology), 1859). This observation was a crucial piece in the puzzle of natural selection, emphasizing the role of geographical isolation in species formation.

The realization that history might be reflected by the geographic association of species is considered one of Wallace’s greatest contributions to the field of evolutionary biology. This idea eventually led to the field of Biogeography, of which Wallace is considered the founding father.

Wallace's transformative moment came during his expedition to the Malay Archipelago. Stricken with a malarial fever, he had an epiphany that would crystallize into the theory of natural selection. "Why do some die and some live? The answer was clearly, that on the whole the best fitted live," he wrote to Darwin in a letter sent from Indonesia. This was a moment of convergence with Darwin, who had been pondering similar questions but had yet to publish his findings.

Shocked by Wallace’s convergence on the theory of evolution by descent with modification by means of natural selection, it was clear that Darwin’s life effort was a risk of being scooped by Wallace. And yet Wallace clearly had arrived at natural selection of his own accord and via honest effort. The solution, developed by Charles Lyell and Joseph Dalton Hooker, who were familiar with Darwin's views and persuaded him not to publish Wallace's essay without including his own long-withheld manuscript.

The result was a paper, entitled "On the tendency of species to form varieties; and on the perpetuation of varieties and species by natural means of selection," which was read at an extra meeting held at the Linnean Society of London. The presentation and the paper read into the record was a joint effort that included extracts from Darwin's manuscript, a letter from Darwin to Prof. Asa Gray, and Wallace's essay. The concept was so monumental there was no discussion following the reading, and the topic was avoided even at tea following the event. The old guard could foresee the conceptual earthquakes, and were likely overcome with preoccupation with issues related to reputation and scorn. (See Wallace’s personal annotated copy of the paper read by Lyell and Hooker, most likely sent to him by Darwin, preserved and scanned by the Wallace Fund).

The letter Wallace sent to Darwin in 1858 was a seminal moment in the history of science. It led to the joint presentation of their papers on natural selection, forever linking their names in the annals of scientific discovery. Wallace was not just a theorist; he was a man deeply concerned with the social and political issues of his time. His later years were spent advocating for a variety of causes, from spiritualism to social justice. Yet, it is his work on natural selection that stands as his lasting legacy. "There is a tendency in nature to the continued progression of certain classes of varieties further and further from the original type," he observed in an essay sent to Darwin with this letter, capturing the essence of evolutionary change.

In the end, the story of Alfred Russel Wallace is one of perseverance, intellectual rigor, and a life dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge. It is a story that deserves to be told, not just as a footnote to Darwin but as a tale of discovery that stands on its own merit. Both Wallace and Darwin were products of their times, shaped by similar influences, yet each brought a unique perspective to the theory of natural selection. Their stories are a testament to the collaborative nature of scientific discovery and the enduring power of curiosity to change our understanding of the world.

In spite of prodding by Lyell, Darwin had been reluctant to publish his ideas without an unassailable encyclopedia of evidence backing them. Russel had noted that there may be a geographic - and therefore historic - component to whatever forces allow "the introduction of new species". Darwin had read Wallace's published essay, but Wallace's "Species Essay"1 was a mirror to Darwin's own unpublished work citing "selection" and noting the relationship between variation in features of individuals and their ability to survive and thrive in any given environment.

Upon receipt of the letter, Darwin was "devastated," but was not defeated. With the encouragement of his friends Charles Lyell and Joseph Hooker, a joint paper was presented to the Linnean Society of London, giving equal credit to both Darwin and Wallace. Darwin's magnanimity was evident; he was willing to share the spotlight with a fellow scientist who had independently arrived at the same groundbreaking conclusion. This is a model for modern scientific inquiry.

Yet it was these very events which prompted Darwin to hurriedly publish "On the Origin of Species" in 1859, which Darwin considered a mere "abstract" of work that synthesized decades of observation, thought, and influence. Yet, he never claimed sole credit for the theory of evolution by natural selection. In fact, in his later years, Darwin used his influence to arrange a government pension for Wallace, ensuring that his collaborator could continue his scientific endeavors without financial worry.

Darwin's and Wallace’s comprehension of the role of natural selection in the emergence of new forms was not just the product of their own genius, but a tapestry woven from the threads of intellectual history and a relentless pursuit of the truth - regardless of the societal and social consequences. It was also a theory that Darwin and Wallace were willing to share, in recognition of the interconnected web of ideas and influences that had led both of them to their own epiphany: that differences in traits related to the ability to thrive and survive in an environment, if heritable, would lead inexorably to change in the species, and could lead to new species altogether.

1 The original manuscript that Wallace composed on the island of Gilolo and sent to Darwin from the neighboring island of Ternate has not been found. It was sent to Darwin as an enclosure in a letter and was subsequently sent by Darwin to Charles Lyell. The only known version of the text is the one published in the Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society (Zoology) in 1859. Wallace's essay was written in February 1858 and focuses on the concept of varieties in species, discussing (among many other concepts) the struggle for existence and the tendency for certain varieties to maintain their existence longer than the original species.

—

Register for “Principles of Evolution”, taught by Dr. James Lyons-Weiler exclusively via IPAK-EDU.org

This article maps the development of the concepts. Here’s a new article rich in details on the voyages of the two men. “Two Distinct Creators”: Comparing Darwin’s and Wallace’s Formative Travels, and How it Influenced their Theory of Evolution

—

NB: This essay could not have been completed without the years of work done by The Alfred Russel Wallace Correspondence Project and the Alfred Russel Wallace Website. I sent a hearty thank-you to George Beccaloni.

The story of how George saved the ARW correspondences is inspirational. The Wallace Correspondence Project (From their website: “Our project has so far located and obtained scans of 5,688 letters, of which 2,748 were written by Wallace and 2,159 were sent to him. The remaining 781 are third party letters which either pertain to him, or were written by Wallace's close relatives and contain information useful to scholars interested in his life and work. The letters were found in 245 public and private collections around the world, and in 245 articles and books. We do not know how many remain to be discovered, but our guestimate is that we have found around 95% of those which survive.”

Check out the presentations and other videos hosted by George on YouTube. To help him continue his academic work on the AWR Projects, email Dr George Beccaloni (Chairman and founder of Wallace Memorial Fund): g.beccaloni@wallaceletters.org

This substack, and its authors are not affiliated with Dr. Beccaloni, the ARW Correspondence project, The Wallace Fund, nor the ARW Website. Factual errors are ours and ours alone.